By: Richard Rapp

rrapp@massgolf.org

The “frequency illusion” describes a cognitive bias, in which a person learns of something entirely new to them, then notices that particular thing with a seemingly odd regularity thereafter.

As a golf writer—a golf writer in Massachusetts, no less—Herbert Warren Wind probably should have been on my radar. He wasn’t, until I read a line from John Updike that referred to Wind and Bernard Darwin as the two greatest golf writers in history. Darwin is a personal hero, so I felt compelled to learn more about Wind. Upon discovering that he hailed from Brockton, I excitedly asked a colleague if he’d ever heard of him.

“Uh, yeah. His old typewriter is currently in transit to our office and he’s in the Mass Golf Hall-of-Fame,” he said. “Oh, and his USGA Bob Jones Award plaque is on my shelf.”

Feeling every bit an ignoramus, I headed down to our small (but growing!) library at Mass Golf headquarters, et voila, two of Wind’s books were waiting on the shelf, plus several co-written volumes, his name etched in tandem with the likes of Nicklaus, Hogan, Sarazen.

It quickly became apparent that Wind’s fingerprints are all over the history of American golf, I’d just been an inept detective. It’s not as though he was flying under the radar with avant-garde, golf adjacent tomes. He wrote a book called The Story of American Golf, after all.

There was one clear option to overcome my shameful blind spot: total immersion.

I dipped my toe in with a series of essays from his long tenure at The New Yorker. I’ve been an on-again, off-again subscriber for years. Periodically drawn in by the quality of the writing, and subsequently pushed away by an inability to keep up with the sheer density of words packed into thrice monthly editions. This cycle has repeated itself enough times that I go to the grocery store with a pile of New Yorker canvas tote bags, which are apparently very effective “renew your subscription” bait.

Aside from a few recent pieces analyzing the geo-political implications of LIV, I have not seen many articles about golf in the pages of The New Yorker, so it was a bit surprising to find how regularly Wind’s columns ran. While a lack of golf writing in the modern iteration of the publication is perhaps a marker of a general shift in the publication’s output, it’s still impressive that Wind was able to engage with a readership that you wouldn’t pin as the type of audience clamoring for a shot-by-shot account of the second nine at the Masters.

In the loftiest sense, people read The New Yorker for incisive articles about wide-ranging, globally scaled topics, in pursuit of a well-rounded intellectual standing (others, of course, read it for the clever cartoons). Wind could speak to that audience because he was a master at situating golf in the world around him, holding it up as an unlikely cultural touchstone that deserved the same amount of consideration as a theater review, or an 8,000 word think piece on the grave dangers of generative AI.

Wind was hardly the first person to receive an Ivy League education in literature before going on to write at The New Yorker, the question is, how did this man from Brockton become the prime author of American golf in its earlier stages?

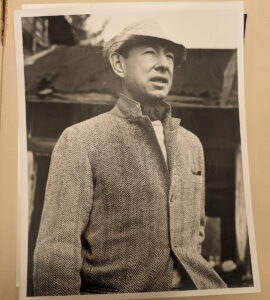

It’s a lifelong journey that started at Thorny Lea Golf Club, where a young Wind fell in love with the game. From there, he went off to Yale University to study English as an undergraduate, then across the Atlantic to Cambridge University, where he earned a master’s degree in literature. Perhaps more importantly, while overseas, he became acquainted with the great Bernard Darwin, a writer who uniquely infused sporting coverage of the game with a literary panache.

Bernard was the first grandson of Charles Darwin, he of naturalism and evolutionary biology fame. Like Wind, Bernard Darwin enjoyed an elite education, first at Eton College before continuing to Trinity College, where he studied law. After finding that a career in law didn’t suit him, he began covering golf for The Times and Country Life.

What probably drew Wind to Darwin, and what continues to draw a particular type of golf fanatic/romantic back to Darwin a hundred years later, is the fantastic collision of his intellect with a maniacal attachment to the game. In more than one essay, Wind recounts the same story about Darwin missing a putt, then promptly dropping to his knees and taking a bite out of the green. It tickles me to imagine that man, turf stuffed in his mouth in a brutish show of temper that, in its extreme, is thankfully not familiar, but as a golfer, I can regard with some amount of twisted empathy. That man, mouth packed with dry Scottish sod, was also a noted scholar of Charles Dickens. Referring to a quote from Middlemarch found within one Darwin article, Wind wrote, “Literary quotations of this type in Darwin are as abundant as parsley on a roast. By far the highest number of them come from Dickens, several of whose books Darwin apparently knew by heart almost from cover to cover.”

It would be difficult to write about Wind without acknowledging the connection to Darwin, not just because Darwin was very obviously an enormous influence on Wind, but because without Wind, Darwin’s work would be much more obscure than it is today. In 1983, Wind co-founded the Classics of Golf Library, which re-issued 69 of the most important works of golf literature, under the discerning direction of Wind. That library was an essential act of preservation, another set of HWW fingerprints on golf’s history, which was so prolifically curated and communicated by one man from Brockton.

As I poked around the internet in pursuit of more details about Wind’s life, I caught a lucky break. An article featuring reproductions of correspondence letters between Wind and some of the game’s greats cited the Herbert Warren Wind collection at Yale as the source.

I promptly registered as a visiting scholar and reserved all seven boxes in the collection. Then, it was off to New Haven with very little idea of what was waiting in those boxes. Could you fit a lifetime into seven boxes?

Bring on the Ivy League. What began as a regrettable bit of obliviousness had turned into something resembling legitimate academic pursuit. I tried to look the part, dressing not quite to the exceedingly dapper standards that Mr. Wind was known for, but at the very least, like a TA squeezing in thesis research between classes.

I arrived on a bright spring day, though, contrary to the bustling campus, the research library was cold, dead quiet, and imposingly efficient. I retrieved the first of seven boxes and found myself a table in the very conspicuously surveilled reading room. The sterility of it all left me a bit uneasy.

As soon as I removed the lid of box one, however, the wonderful world of Herbert Warren Wind burst to life. It was tangible and dusty and personal. Wind had fastidiously chronicled life’s details, large and minute, in looping script. Sometimes neat, sometimes illegible. He’d saved notebooks of different shapes and sizes. A few were year-long diaries, in which he dutifully recorded his thoughts, every single day. Others were notepads that had clearly been tucked in his pocket on the golf course, with scribblings about holes, shots, and galleries. Even a sketch of a woman’s face that must have caught his eye.

The contents of the boxes were intimate to the extent that reading his entries began feeling like correspondence with a friend. In 1940, a 24-year-old Wind grappled with a creative rut, “I am writing with a disgusting lack of flexibility these days. Every other sentence says but, or even or it or this or more,” as well as the state of his golf game, “with my woods I am a 72 golfer, with my irons an 82 golfer, and with my putter a 102 golfer.” I wanted to put an encouraging hand on his shoulder, but settled for the cool steel of his monogrammed cigarette case, which was a memento from his time writing for the Yale Daily News in 1937.

There was a notebook in which he reviewed the books on his shelf; the inside cover read: “Short impressions on the books I have read – plus the dangerously original H.W.W. marking system.” There were movie reviews and golf course reviews, it seemed that anything Wind encountered in the world triggered a compulsive need to react, analyze, then situate within a larger context.

That compulsion was borne out in his writing, and I believe it’s what made him so adept at penning a coherent and comprehensive account of golf’s history in the United States. The game’s popularity spread like wildfire in the early part of the 20th century, with courses sprouting up everywhere, larger-than-life players jostling for headlines, national tournaments taking shape, and equipment evolving. Wind made sense of it all, capturing the excitement of rapid progression, while dutifully preserving the game’s early history. Ever situating.

There was also a book of Edward Hopper prints, which struck me as an odd inclusion in a personal collection. But the connection makes sense when you consider how deeply emblematic of early-to-mid-20th century Americana Hopper’s paintings are.

Wind may have idolized Bernard Darwin, but there’s nothing of the caustic British wit and thumping personality of that old master in the writings of Wind. Wind’s writing is often reverential of towering American golfers, but despite his personal relationships with many of those figures, there’s a careful remove. Like the perspective in Hopper’s “Nighthawks,” he places the reader at an intentional distance, outside the diner (or ropes, as it were). Profiling the early greats like Vardon and Jones amounted to erecting the immense skyscrapers that framed Hopper’s canvases. You might catch a glimmer of your reflection in their austere windows, but ultimately, they exist on a different scale.

Did Wind, living alone in New York City, also feel some of the modern isolation that Hopper so deftly portrayed? Sorting through photographs and old passports, clipped reviews of his books and warm letters from acquaintances (everyone from Bing Crosby to President Eisenhower), I got the sense that despite his proximity to the heart of the game, holding the stethoscope and recording its thrums, Wind worked as a lone wolf. Yes, he had many friends, but he was never married or had children, and with pen and pad in the center of the maze, he was somewhat isolated in his pursuits.

To be clear, the remove from which he wrote was not a drawback. His deferential recounting of the accomplishments of elite players helps elevate the extraordinary aspects of the professional game. In his personal writing, Wind’s admiration of Bobby Jones sings. In his public writing, he is more restrained, but still spotlights his hero by positioning him on a larger stage. With Jones, we can find a telling example of how Wind and Darwin achieved brilliance in completely different styles and perspectives.

Darwin lyrically offers his personal admiration for Jones from the perspective of an aficionado:

“There was a strain of poetry in Bobby.”

“There was nothing hurried or slapdash about it and the swing itself, if not positively slow, had a certain drowsy beauty which gave the feeling of slowness. There was nothing that could conceivably be called a weak spot.”

Wind captured Jones’ stature by describing the way the town of St. Andrew’s embraced him. It reminded me of the way Hemingway described Spaniards embracing the best toreros. Jones wasn’t merely a star athlete to those people, his mastery of golf and his approach to the game forged a connection directly to the hearts of the Scottish people. Artistry and skill, but also dignity.

One of the more moving instances of Wind’s writing can be found in his essay “St. Andrew’s and the British Open.” Wind describes a scene in which Bobby Jones, after many years away, returned to St. Andrews to captain the American team in the World Amateur Team Championship for the Eisenhower Trophy in 1958. A ceremony was held by the city, as Jones was named Freeman of the Burgh of St. Andrews, the first American to receive the honor since Benjamin Franklin.

“At the end of his talk, Jones left the stage and got into the golf cart he used to help him get around. He guided it slowly down the center aisle of the hall. As he did, the whole auditorium suddenly erupted in the most stirring rendition imaginable of the old Scottish song “Will Ye No’ Come Back Again?” It had all the strange, wild, emotional force of the skirl of a bagpipe. Hardly a word was said as the people filed from the hall, and for many minutes afterward it was impossible for anyone to speak.”

Wind places the reader in that hall just as he places them on the rope line at Augusta. He was a spectator of the world, as well as a chronicler of it, and used his watchful eyes and innate curatorial sense to relay what was most important and where it fit.

If, like me, you were unfamiliar with his work until recently, I hope this article helps you catch a case of the Wind. You may find that in the world of golf, the inscription HWW is perpetually imprinted on the next page you turn to. I’ll leave you with an excerpt from his 1964 article “The Third Man,” which I believe displays the best elements of Wind’s writing:

“A little sun would not hurt now. I shall never forget the expression on his face as he came down the hill. It was taut with fatigue and strain, and yet curiously radiant with pride and happiness. It reminded me of another unforgettable, if entirely different, face – the famous close-up of Charlie Chaplin at the end of City Lights, all anguish beneath the attempted smile. Venturi then put his cap back on and hit those two wonderful shots.

Few things repair a man as quickly as victory.”

Mass Golf is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization that is dedicated to advancing golf in Massachusetts by building an engaged community around the sport.

With a community made up of over 123,000 golf enthusiasts and over 360 member clubs, Mass Golf is one of the largest state golf associations in the country. Members enjoy the benefits of handicapping, engaging golf content, course rating, and scoring services along with the opportunity to compete in an array of events for golfers of all ages and abilities.

At the forefront of junior development, Mass Golf is proud to offer programming to youth in the state through First Tee Massachusetts and subsidized rounds of golf by way of Youth on Course.

For more news about Mass Golf, follow along on Facebook, X, Instagram, and YouTube.