By Steve Derderian

sderderian@massgolf.org

Labor Day rarely shows up as a marquee date on the golf calendar, aside from marking the end of summer golf or yearning to bring back those feelings of Monday afternoon final rounds at TPC Boston when galleries spilled all the way down the ropes, hoping to catch a glimpse at Tiger mid-charge.

Yet, despite its lower profile in golf, Labor Day provides an opportunity to consider the important, though often overlooked, role that its workers play in the game.

The expansion of the game during the 1920s and 1930s witnessed the heyday of the schoolboy caddy, with many coming from families where the money they earned caddying was needed to help make ends meet. Private clubs prided themselves on decorum and hierarchy, but every so often, that order cracked. It wasn’t under pressure from union bosses or labor lawyers; rather, it was from teenage boys, sunburned, sore, and tired of being overlooked.

At clubs statewide, they demanded better. And sometimes, they got it.

_

Caddying itself has deep roots, stretching back to 18th-century Scotland. The word originated from the French “cadet,” and in Scottish tradition, a caddy was originally an all-purpose helper, serving as part porter, part groundskeeper, and part apprentice to the club professional. Early pros were often tradesmen who made and repaired wooden clubs and balls, and senior caddies were on track to become one of them.

But by the 20th century, as golf began to take shape in the U.S., that apprenticeship had been reduced to a narrow service role, carrying increasingly heavy bags for little pay. Managers typically claimed caddies weren’t employees, but imposed strict rules, regimens, and discipline. At many places, caddies had to check in at the shack, wait in line for assignments, and were docked pay for missteps. Pay was set annually by club committees. Tipping was often banned. Attendance, not ability, often determined end-of-season bonuses. In practice, many clubs operated surplus labor systems that made earning a steady income difficult, especially for young people.

In 1905, one of the earliest reported caddie strikes in the state broke out west at Lenox Country Club. The boys held the line for three days, demanding 25 cents for nine holes instead of 20. The club refused, and the strike ended with the caddies returning empty-handed. “We had to beg to get back to work,” one of them recalled years later.

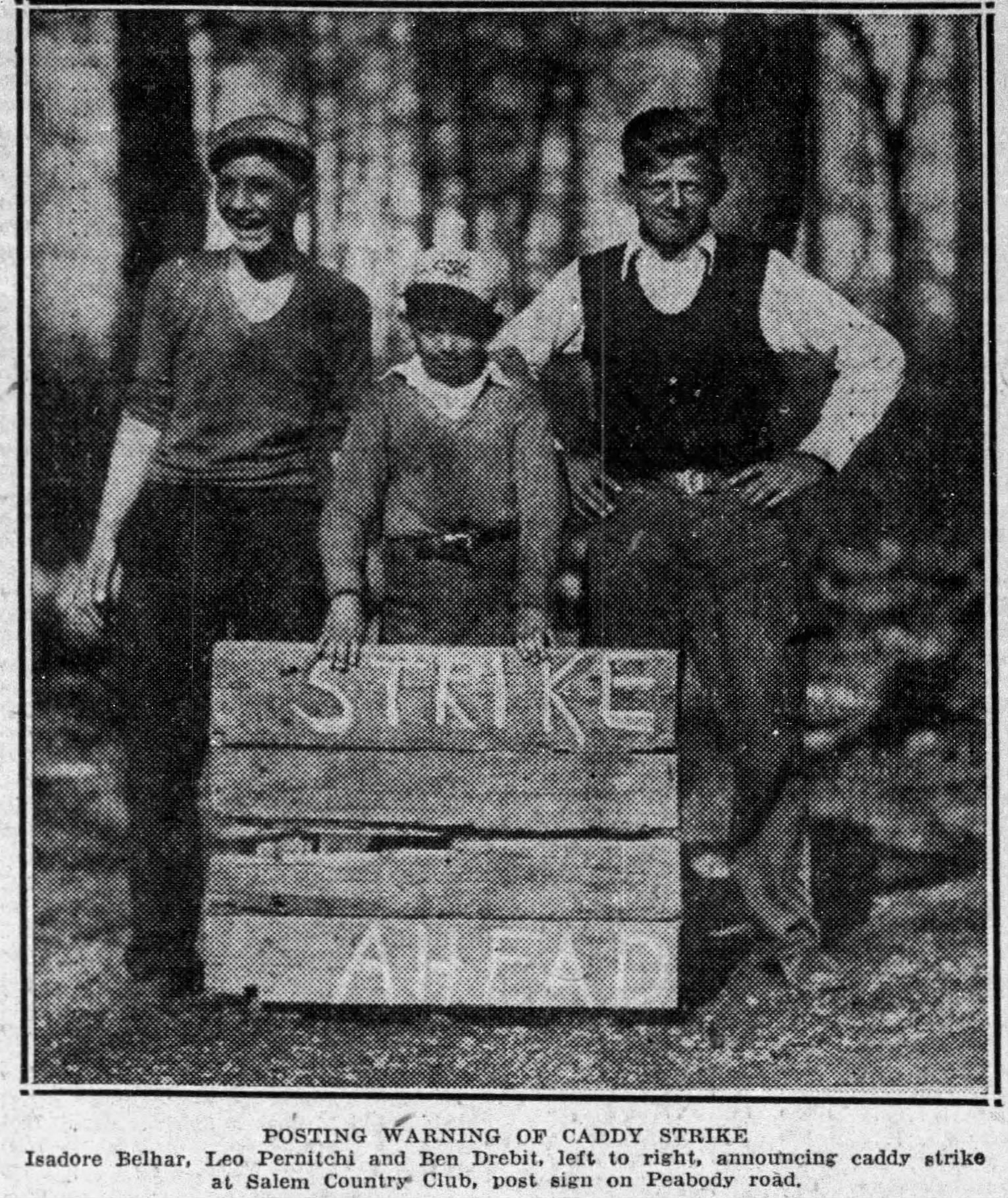

With the proliferation of golf between the First and Second World Wars, caddie protests grew bolder. In May 1933, nearly 200 Salem Country Club caddies walked out after their caddymaster was removed and pay was cut from $1.20 to 80 cents per round. The dispute wasn’t just about money: a new lottery system replaced the traditional first-come, first-served approach, frustrating the most dedicated caddies.

The club tried using stand-ins from nearby towns, but they were eventually sent home.

Among the observant membership was Salem women’s champion Mrs. H.H. Hicks, who defended the caddies, calling them “sheep in wolf’s clothing.” Her main concern was what she called golf’s “tonnage” problem, the oversized bags and players’ reliance on caddies out of habit. Hicks had hauled her own clubs for years and wasn’t impressed by golfers who treated caddies like invisible labor. To Hicks and many fellow supporters, caddies were subject to a backdoor, outdated system, or as she eloquently put it, “Today, caddying falls in the same general category as bootlegging beer.”

In Concord, 22 caddies struck in 1937 over changes that introduced a tiered pay system: 75 cents per round for Class A caddies, 65 cents for Class B. Club officials insisted the classification was fair and emphasized new perks like radios and ballgame trips. However, the strikers saw it differently: the new rules made it harder to get promoted, and for many, the loss of the old flat rate was tantamount to a pay cut.

That same year, a walkout at the Country Club of Pittsfield was defused only after police warned the boys about the potential for inciting trouble. After a visit from the club pro and a meeting with the president, the strike ended with the boys agreeing to a trial of the new system. Pay would be based on a rating system marked “Good,” “Fair,” and “Not Good.” To earn a promotion from Class B to Class A, a caddy needed endorsements from three members. The hope was that this would provide incentives, but the boys had struck in the first place because unequal pay and favoritism were already core grievances.

In both 1940 and 1941, dozens of Pittsfield caddies walked off again. This time, they demanded $1 per round for Class A caddies, with 10 cents going back to the club. By the end of Fourth of July Weekend in 1941, the club relented, raising pay and granting additional concessions.

The postwar years introduced another shift. Organized labor movements around caddies weren’t as prevalent as clubs struggled with wartime neglect. Tournaments that had been paused or diminished needed time to regain their prominence.

However, there was one example in 1947 that drew the attention of the state’s labor department. Caddies at South Shore Country Club in Hingham sought $1.35 per round, as 10 cents of the current wage of $1.10 was being pocketed by the caddy master. While state officials considered a broader ruling that might affect every golf course in Massachusetts, the caddies won their raise in just 24 hours and returned to the course on July 19, 1947. A similar one-day strike at Tedesco Country Club in Marblehead ended with caddies scoring a 25-cent raise.

Not every protest succeeded. A short-lived strike at Taconic Golf Club decades later fizzled out in 24 hours. Twenty-five caddies walked off, reportedly after a broken-up card game, but only one stayed out. The lone holdout, described as the ringleader, was asked to leave the course following a tirade directed toward pro shop staff and likely everybody within earshot.

Elsewhere, cooler heads sometimes prevailed. At Oak Hill Country Club in Fitchburg, a spontaneous walkout ended after police intervened and a town official convinced the boys to appoint a committee and negotiate properly. The new system agreed upon included evaluations and promotions, aiming to bring fairness without further disruption.

__

Today, approximately 30 Massachusetts clubs still operate traditional caddie programs ranging from small upstarts to longstanding programs of 60 or more kids. Clubs like Worcester Country Club, Concord Country Club, The Kittansett Club, and Sankaty Head Golf Club have not only preserved the tradition, but they’ve also elevated it. Structured systems, fairer pay, and networking and scholarship opportunities reflect a deeper commitment to the next generation. As such, they have maintained a tremendous relationship with the Francis Ouimet Scholarship Fund, which awarded $3.4 million in student aid for the 2024-2025 academic year.

The caddie strikes of the early 20th century proved that even the youngest workers understood the value of their labor, and they were willing to lay down their clubs to stand up for it.